Aug. 15, 2022 — The Inflation Reduction Act passed last week may represent the best outcome the biopharma industry reasonably could have hoped for at a time when so many in Congress are eager to respond to strong public opinion that prescription prices are too high. The new legislation, which reins in some drug costs over time through Medicare price negotiation, limits on patient spending and caps on price increases, also includes an increase in federal health spending.

Specifically, the Inflation Reduction Act includes roughly $386 billion in new spending on measures to address climate change, $98 billion in health spending (including extending enhanced Affordable Care Act [ACA] subsidies), and about $305 billion toward reducing the federal deficit. These are paid for by tax measures primarily affecting large corporations, and savings to the government from measures to reduce what Medicare spends on prescription drug prices.

The bill was passed using the “budget reconciliation” framework from President Joe Biden’s initial Build Back Better proposal, thus requiring only 50 votes (plus Vice President Kamala Harris’ tie-breaker vote) in the Senate rather than the usual 60. To get those 50 votes and comply with rulings by the Senate parliamentarian, most of the prescription drug provisions apply only to the 18 percent of the population covered by Medicare.

Biopharma benefits from an increase in the population able to afford medical care. The bill extends for an additional three years the more generous subsidies for ACA insurance plans and an expanded threshold for eligibility that were first enacted in the American Rescue Plan last year. These measures –which the Department of Health and Human Services reports led to 5.8 million new enrollees in ACA plans – had been scheduled to sunset in December.

Slow roll for Medicare drug price negotiation

“The new legislation includes, for the first time, authorization for Medicare to negotiate the prices of prescription drugs, but the impact was watered down by a number of compromises during negotiations,” according to Coalition for Healthcare Communication Executive Director Jon Bigelow.

In a Coalition alert to industry leaders, Bigelow noted that initially, 10 high-priced drugs covered under Medicare Part D will be included; the negotiated prices will not take effect until 2026. An additional 15 drugs will be added in 2027. In 2028, 15 drugs (Parts B and D) will be added, then 20 more in 2029. Products included will have been on the market for at least nine years (or up to 13 years for biologics). A product will be removed from the list if a generic or biosimilar comes on the market. The negotiated prices will apply only to patients enrolled in Medicare.

“Clearly, this is the most controversial element of the legislation,” Bigelow said. “Medicare negotiation would reduce the price of some of the most expensive drugs for which competition has not developed.”

The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) argues that allowing even this limited scope for Medicare negotiation (which it says is tantamount to setting price controls) will markedly decrease development of innovative medicines by changing the financial incentives to invest in promising molecules.

However, the Congressional Budget Office estimates that the actual impact will be small – over the next 30 years, only 15 (1 percent) of 1,300 new drugs would fail to come to market. Bigelow explained that some market observers anticipate even less of an impact than that, pointing to the range of other incentives to develop new medicines. The bill’s supporters estimate $99 billion over a decade in savings on drugs from negotiations.

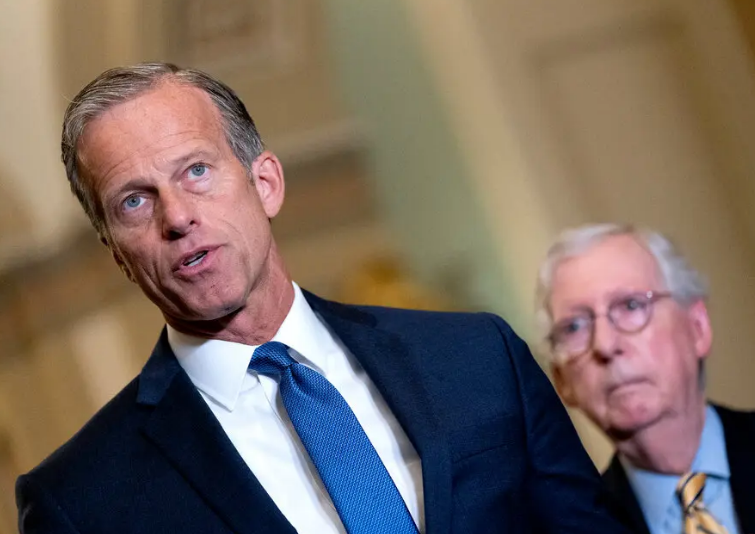

“On the other hand, there’s a question whether a precedent has now been set that will lead to Medicare negotiation on a broader range of prescription drugs or to extending the negotiated prices to the much larger commercial insurance market,” Bigelow remarked. “With the current consensus that Republicans are likely to take control of the House after the midterms, it seems unlikely that the scope of negotiations will be widened in the immediate future,” he said.

Price, spending limits apply only to Medicare

Under the new law, a stiff penalty will be imposed if a prescription drug’s price is raised above the rate of inflation—but again, only for patients on Medicare. Efforts to provide a similar penalty for private insurance plans were defeated.

Half of prescription drugs taken by Medicare patients saw price increases higher than inflation in 2020, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF), so this provision could have some bite. The bill’s supporters estimate $101 billion in savings over 10 years. Some analysts speculate that biopharma companies may respond by setting launch prices higher.

The Inflation Reduction Act also will limit to $2,000 per year the maximum out-of-pocket cost of prescription drugs for patients covered by Medicare, beginning in 2025. KFF reports that 1.4 million Medicare recipients spent more than this in 2020. There is also a specific cap on out-of-pocket spending on insulin, at $35 per month, beginning in 2023.

These measures, too, will apply only for patients outside of Medicare. According to the Census Bureau, 54 percent of Americans with diabetes were in employment-based insurance plans in 2020. An amendment to extend the out-of-pocket cap on insulin to these patients won the votes of seven Republican senators; Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) says he will bring this issue to a separate vote later this summer.

How much will things change?

PhRMA has threatened legal action to block or delay implementation of the prescription drug pricing measures. It also hinted strongly that it will campaign against vulnerable Democratic members who voted for the Inflation Reduction Act.

Still, with the Senate sure to remain closely divided after the midterms and with polls showing Republican as well as Democratic voters concerned over prescription drug prices, “it is difficult to see enough members voting next year to repeal the measures just enacted,” according to Bigelow. “But remember, the negotiated prices won’t be implemented until 2026—and the situation in Congress and the White House may look different then.”